|

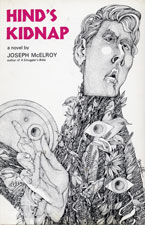

Hind's Kidnap. A Pastoral on Familiar Airsby Joseph McElroy Edition History:

|

|

A very tall man resumes his search for a kidnaped child long after the unsolved case has been officially closed. Hind dropped his search when he married. Now, some years later, at the instant the novel opens, he is leaving his apartment to visit his estranged wife Sylvia and his five-year-old daughter May; he wants to live with them. But at his door is a strange old woman, and in his mailbox a note beckoning him toward the old trail. Hind’s renewed quest leads him among people in their spring and early-summer landscape – a city pier; the well-fenced office complex of a famous firm; a New England golf course and the owner’s house overlooking it; a city health club; and a city university. Yet at the end of this pentad the kidnaping of the child, Hershey Laurel, has receded to a dim corner of the book. And Hind’s late, beloved guardian, and the threatening past he summons up, grow more and more powerful, uncontrollably, as does Hind’s awareness that his search has taken possession of him. Hind realizes, too, that despite his craving to be needed, he has used people as means, abbreviated them as clues, and disposed them in his heart as exhibits. He becomes unsure whether he wants to go back to Sylvia because the fifth clue points to her or because she is a woman he loves. He revisits his friends, his clues, in the hope of "taking" them not as clues but as ends in themselves. Indeed, he endeavors to de-kidnap them. But what has been started – and only partly by Hind – can’t be stopped. The lock pursues the keys, the kidnaping pursues the memory that is trying to erase it, and a mass of old life emerges – passionate adolescence, the cruel charm of the clever, sickly girl Hind adored, the intricate commitments to childhood friends, and, in back of it all, the guardian himself, a failure, a remotely tragic hero, an interesting man. The maze of the book’s opening part has come into focus out of its dense nightmare anonymity – New York, Brooklyn Heights, terrible genealogy, the self in relation to others. |

|

Reviews for Hind's Kidnap. A Pastoral on Familiar Airs |

|

|

Robert Adams New York Times Book Review Jan. 1970, ... The web of his suspicion gets ever larger and more complicated. People seem to have "messages" coded into their minds that they know nothing about, but that they'll release in a casual word or gesture if Hind will just wait around long enough for them to let go. The trail branches out in a wilderness of directions, and Hind, with the infinite patience of obsession, sets out to run them all down. Sylvia, his wife, not unnaturally gets somewhat impatient with this search; on the other hand, Hind's menagerie of unofficial welfare clients proves a rich store of leads, and he is anxiously dreamily tracing them out, when one of them points him back to Sylvia. She tells him that he is making unjustified use of people in his plot, treating them as receptacles for bits of evidence, not legitimate ends in themselves. Nothing if not suggestible, Hind takes the lesson to heart, and embarks on a counter-project, no less elaborate than his original program, but aiming this time at "de-kidnapping" all his victims. ... Scenes of academic and industrial parody achieve a grotesque and wonderful absurdity -- they're the open spaces of the book, and very welcome indeed. There is a lyric flow to Mr. McElroy's prose when he lets it go that overrides if it doesn't obliterate the verbal patter-work, and leaves the pronouns hanging where it doesn't matter about their antecedents. Even the puns and distortions and word arabesques of the post-Joycean art-style (which can so easily look cute) and the cataractic involution of the underpowered, overloaded sentence (which probably owes something to Faulkner) take on expressive qualities. When he wants to use them, Mr. McElroy has in his repertoire a vivid, evocative vein of language and a fine, throwaway wit; but Hind and his Sylvia, through the watery currents of their sleepspeech will sometimes strike the reader as talking too directly to themselves. |

|